And she built a church—a vast construction, like nothing anyone had ever seen in any city of Christendom. Honoring the martyr Polyeuctos, it stood on a rise of ground along the main processional street of Constantinople that stretched west from the palace and then turned northwest through the heart of the city. Juliana planted her own church just past the turning, forcing it onto the most public stage set of empire in a central role, advertising her wealth and her piety equally. In the tenth century, the emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus knew the church well and described the processions he took part in that went past the bakers’ quarter, and how he paused by Polyeuctos’s and Juliana’s church to get a fresh candle to light his pious way to the church of the holy apostles at the top of the rise a little farther out on the main avenue. Juliana’s church building collapsed in the twelfth century and was all but forgotten.

Roughly square

Roughly square in form with a domed central space, it measured about 175 feet on a side—approximately the size of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue or Saint Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue in New York. The dimensions of the building are important, because they closely match those of Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem as reported in the Christian Bible communist bulgaria tour.

Juliana’s pride and piety echo for us in the text of a forty-one-line inscription that ran around the basilica’s central space and glorified both the builder and her aims. Fragments of that inscription, which were long known from manuscript copies taken down by an admirer, made it possible to identify the remains of her church when excavators found them during an urban construction project in i960. The great inscription ran around the church in letters four inches high, a line each on a series of arches, surrounded by elaborate vine leaves and each arch itself filled with an ornate, elaborate carved peacock’s tail; several of those arches, each about nine feet across, survive. The inscription begins:

Eudocia the empress

Eudocia the empress, eager to give honor to God, first built a temple of Polyeuctos the servant of God: but not one like this, not one so huge. It was not that she was ungenerous or lacking in wealth—what can a queen lack?—but she was endowed with a prophetic spirit, to know she would leave offspring who would know well how to fit it out better.

It showed no impiety to outdo one’s ancestors in this manner, especially while outdoing one’s contemporaries to advance the family name.

From among them Juliana, shining light of God-blessed parents, fourth in the line of that royal blood, did not belie the hopes of the queen who left such splendid children. She raised up a small temple to the great and glorious one here, augmenting the glory of her many- sceptered forebears, bearing the orthodox faith of a zealous lover of Christ. Who hasn’t heard of Juliana, how she made her parents glorious by her well-made works, pious as she was? Transit Gloria Mundi

By the time this church was built, of course, no one could fail to know the name. And not only in Constantinople:

You alone built countless churches in every land, ever fearing the servants of the God of the sky.

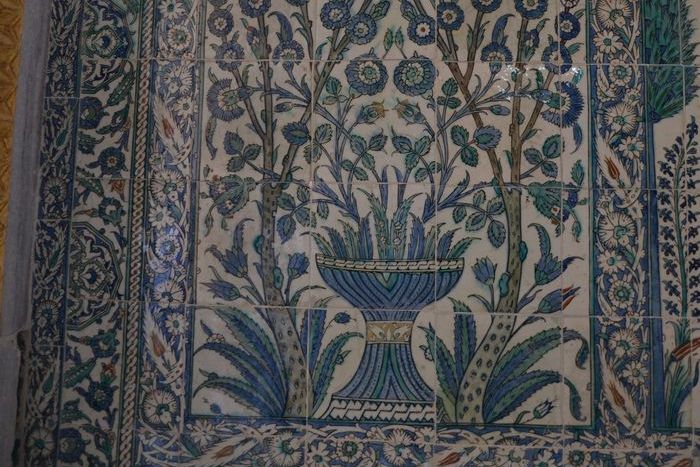

The apse arching over the altar was decorated with human figures on a gold background, and there were mosaics and sculpture everywhere, including busts of Christ, the Virgin, and the apostles. Later in the sixth century, the bishop of Tours in Gaul, Gregory, wrote in one of his histories how Justinian envied Juliana’s riches and her gold, so she promised him that he could take what he liked—but then she had it melted down to decorate her church before he could take possession and he was too embarrassed to complain. She gave him a small ring as consolation. Although Justinian eventually built bigger churches, the sting of the snub lingered. Building well was Juliana’s best revenge for her husband’s downfall.